News

The integral role that shared learnings play in the ongoing efforts to end female genital mutilation/cutting (FGM/C)

As part of our project funded by the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs, I joined a workshop that brought together nine organisations implementing end-female genital mutilation and cutting (FGM/C) grants across Sub-Saharan Africa.

The workshop, run by Orchid Project, was an opportunity for these grassroots and civil society organisations to share their experiences, challenges, and learnings from the past six months. Having connected in previous workshops, the grant holders were enthusiastic to update and reconnect with each other, creating a vibrant and dynamic conversation. Such sessions provide a tangible sense of the power of movement building, and the integral role that shared learnings play in the ongoing efforts to end FGM/C.

One of the discussion points for the organisations was the need to identify and engage with key stakeholders at the beginning of their projects. This aligns with the theory of change for the grant portfolio, which identified community buy-in and trust as imperative for bringing about sustainable social-norm change. However, it was fascinating to see the variety of ways this has occurred in differing contexts.

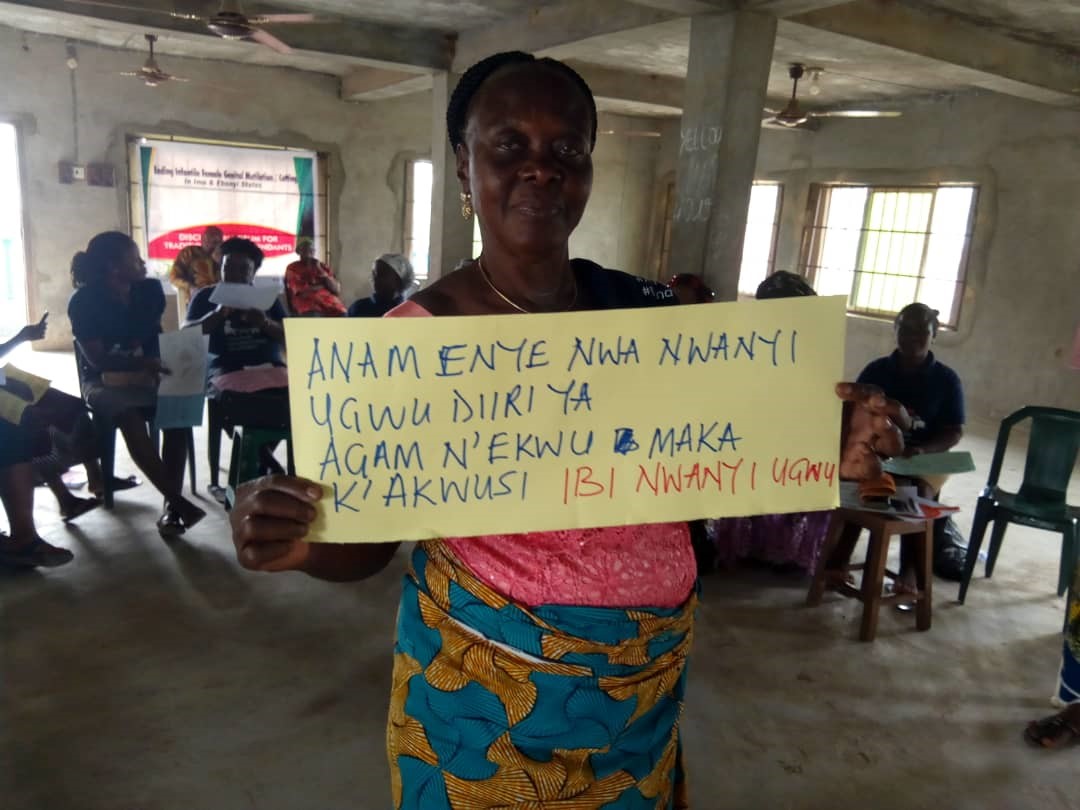

A grantee from Circuit Pointe in Nigeria was the first to share their experience: she highlighted how her organisation has built on existing social structures, along with using radio and social media, to inspire key influencers at the community level to speak out against FGM/C. Circuit Pointe’s main target audience was traditional birth attendants, who are often responsible for performing FGM/C on newborns as part of their birth services. By involving them in community dialogues, it is hoped the practice on newborn babies will reduce.

Engaging influential stakeholders helps to mitigate against backlash to changing embedded practices, and Women’s Action for Human Dignity (WAHD), based in Sierra Leone, spoke about successfully recruiting and training men and boys as champions to discuss the topic and create community support. By working with respected and influential men within the communities, WAHD has been able to involve initially sceptical male leaders in the movement.

Religious leaders also have a powerful role to play in changing the practice of FGM/C, as highlighted by the Kenyan Council of Imams and Ulamaa, which has engaged and worked with Islamic leaders to share stop-FGM/C messaging. Imams have spoken out against FGM/C in their mosques and communities as a result, sending a powerful message to those who believed FGM/C was necessary as part of their Islamic faith.

All organisations inevitably faced challenges in their outreach but shared the solutions they found to overcome them. As a closing point, one grantee from Nigeria highlighted that some communities expect ‘saviours’ and want support with multiple aspects of their lives, which go far beyond the grant’s scope, such as the provision of money and medicine. It was agreed that in such situations, support can be given by recommending other organisations that may be able to help. However, there was also a reminder that in these cases, especially considering the extra pressures of the last year, activists and organisations must look out for their own wellbeing so they can continue to make positive change by supporting an end to FGM/C.